Lessons From Rwanda Genocide: Avoid Ethnic Stimulation, Sensationalizing Political Reports

By Chuka Nnabuife | ANCISRO

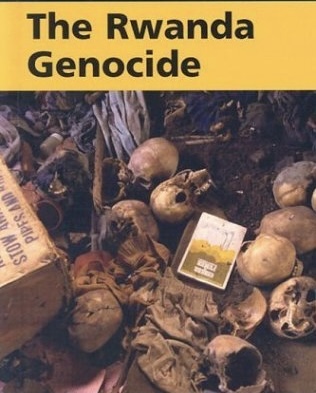

The Rwanda Genocide of April 1994 clearly highlights the crudity, savagery, and man’s capacity to succumb to the negative energies of hatred and blind headiness. One of the events in modern Africa’s history that clearly establishes the grave danger in abusing the use of mass media space comes up for memory today. Coming up at a time when the abuse of mass media is rampant and increasing, it is especially worth pondering how political propagandists put a land literally on fire.

The Rwanda Genocide is a worrisome reminder of the direction misinformation and disinformation can lead a people, even with their eyes wide open. The saga that sadly highlights where we are likely heading happened exactly 31 years ago. Today marks the 31st anniversary of the havoc sadly recalled as the Rwanda Genocide, which found the majority Hutus of the three ethnic nationalities in Rwanda raging against the minority Tutsis and massacring them to the chagrin of the entire world.

In marking its 31st year of passage, the world, through the United Nations, has set out April 7 through April 21 for remembrance events. Similarly, the nation of Rwanda and other countries are going down memory lane on the development to emphasize why it must not happen again.

The Rwanda Genocide was such a shocking slice of history that, apart from the social cohesion and political leadership in the country, which were its primary casualties, even Christianity and colonial legacies were rattled badly by it, but worst-hit was the integrity and relevance of the mass media.

Rwanda is a nation made up mostly of two ethnic nationalities: the majority Hutu of larger population and the minority Tutsi, which constitutes mostly the country’s elites. Given that upon the end of European colonialism in Rwanda, the Belgians handed the leadership of the country over to the Tutsi, an ever-rumbling setting where the Hutu, who are more in population, is engaged in an unending combustive relationship with the Tutsi was birthed.

As contemporary historians recall, the Hutu versus Tutsi political row had been recurrent in Rwanda since the 1950s, and the exit of the Belgians aggravated it. There is also a third ethnic nationality in Rwanda named the Twa, but the population and furore between the Hutu and the Tutsi tend to douse the appearance of the third ethnicity in the news.

Mostly, the Hutu, despite being in the majority, claim the Tutsi marginalize them given that they are mostly in the ruling class. In 1994, an elected president of Hutu nativity, Juvénal Habyarimana, was killed on April 6, 1994, in suspicious circumstances, and all hell broke loose as the country’s soldiers, who were mostly populated by Hutu youths, and a youth wing of the ruling political party evolved into a restive militia, the Interahamwe.

The land was engulfed in tension, but the immediate spur of the genocide was one momentary error of indiscretion by some widely followed media broadcasters. They encouraged a bloodthirsty charged section of society to vent; they profiled and stigmatized the Tutsi elite. People bought their messages hook, line, and sinker, armed, and rushed after the Tutsi with machetes, axes, and cudgels.

In hours, heads rolled, blood poured like flood on the streets. Even children, women, and the aged who rushed to seek refuge in the thitherto serene and safe sanctuary of churches were besieged there and hacked down. Between 10,000 and 45,000 persons, comprising mostly Tutsi and moderate Hutu, were killed from April 10 through 15, 1994, at a Catholic church in Nyamata, Rwanda. Women, including nuns, were raped.

The killers were on a rampage, and broadcasters of such stations as the then-popular Radio-Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) and writers in Kangura Newspaper were keenly releasing messages demonizing and dehumanizing the Tutsi people. Soon, the whole nation was turned into a slaughter field that recorded over one million deaths in just 100 days.

A section of the media gleefully played conspicuously odious roles in the Rwandan Genocide. Under the guise of possibly serving what a section of their audiences wanted, they incited violence and spread propaganda against the Tutsi minority, as well as the Hutu and Twa who did not support the campaign of calumny.

RTLM and Kangura newspaper used hate speech and propaganda, not just to dehumanize the Tutsi but clearly called for their extermination. RTLM, an influential broadcast channel, added the element of frightening the uninvolved by suggesting that there was a monitoring squad of Hutu extremists who would carry radios and machetes, ready to start killing once the order was given. The media created a sense of urgency and fear among Hutus, framing Tutsis as a threat and justifying violence against them.

RTLM broadcasts often included specific details about Tutsi locations and identities, making it easier for perpetrators to target them. RTLM and other media outlets played a crucial role in mobilizing and entertaining Hutu extremists and provided them with information and inspiration. The radio station broadcasted 24 hours a day during the first ten days of the genocide.

The interim government, controlled by hardline Hutu politicians, and rebels of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) used media to feed international channels with misinformation, portraying the killings as “tribal conflict,” whereas it was a spate of planned killings, not war.

The Rwanda debacle exposed how the media can be an open associate in a crime against humanity. After the killings and investigations by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, among those convicted were several media leaders, including RTLM co-founders Ferdinand Nahimana and Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza.

They were charged and found guilty of genocide, incitement to commit genocide, and persecution. Thus, establishing the media’s roles in fueling hatred, mobilizing perpetrators, and exacerbating violence against the Tutsi minority.

During the Rwandan Genocide, for example, the term “cockroaches,” popularized by the media, was used as a derogatory and dehumanizing label to refer to people of the Tutsi ethnic group. This term was often used in propaganda and hate speech to incite violence and justify the killing of Tutsis.

The use of this term was particularly prominent in RTLM broadcasts. It made it easier to justify violence and extermination against the victims. Among the horrors from the crisis is not just that hatchet media men were ventilators of it; there were women too.

All of them were highly placed people who ordinarily should know the import of their actions. Among individuals jailed for their roles in the Rwandan Genocide was Beatrice Munyenyezi, who was sentenced to life imprisonment. She was found guilty of ordering murders and attacks, including the rape of a nun, and identifying Tutsi people to be killed at a roadblock in Huye, Butare.

Emmanuel Ndindabahizi, sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide and crimes against humanity, was a former Minister of Finance in the Interim Government of Rwanda. He was convicted of instigating attacks against Tutsi refugees, distributing weapons, and encouraging killings.

There is Wenceslas Twagirayezu, who got a 20-year sentence for genocide crimes. Twagirayezu, a former lecturer, was found guilty of genocide offenses in seven areas of Gisenyi town, including Mudende University and Busasamana Catholic Church.

These sentences were handed down by Rwandan courts and international tribunals. But the essence of the whole narrative is to establish that the havoc is not just the handiwork of those who do not know the import of their actions but the individuals and organizations that should know the outcome of what they did.

This brings to the fore the relevance of the anniversary of the genocide in this vexed era of rabid media manipulation, social media disregard of facts, and ever-rising reign of misinformation. Across the world, especially in countries like Nigeria, the media is increasingly succumbing to the lure of populism and the crave to increase market reach by sensationalizing the news.

Some broadcasters and reporters even get deliberately carried away by the lure of popularity and the crave to be celebrities, but journalism and a sane society require more than fame. Thirty-one years after, the Rwanda Genocide presents a clear pointer to where we may be heading in societies where propagandists and ethnic jingoists have taken over the space for political communication, like in Nigeria.

In lands like Anambra State, where an election season is now in the cusp, the lessons from 1994 Rwanda are: tread carefully before you set the land ablaze with incautious reports.

ANCISRO is Anambra State Civic and Social Reformation Office